Explorer 1

|

|

| Operator | Army Ballistic Missile Agency |

|---|---|

| Major contractors | Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

| Mission type | Earth science |

| Satellite of | Earth |

| Launch date | 1958-02-01 03:48 UTC |

| Carrier rocket | Juno I |

| Mission duration | 111 days |

| Orbital decay | 1970-03-31 |

| COSPAR ID | 1958-001A |

| Homepage | NASA NSSDC Master Catalog |

| Mass | 13.97 kg (30.80 lb) |

| Orbital elements | |

| Semimajor axis | 7,832.2 km (4,866.6 miles) |

| Eccentricity | .139849 |

| Inclination | 33.24° |

| Apoapsis | 2,550 km (1,585 miles) |

| Periapsis | 358 km (222 miles) |

| Orbital period | 114.8 minutes |

| References: [1][2][3][4] | |

Explorer 1 (1958 Alpha 1)[5] was the first Earth satellite of the United States as part of the program for the International Geophysical Year and in response to the launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1. It was launched on 31 January 1958 at 03:48 UTC atop the first Juno booster from LC-26 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida. It was the first spacecraft to recognize the Van Allen radiation belt.[6]

Contents |

Mission

The U.S. Earth satellite program began in 1954 as a joint United States Army and United States Navy proposal, called Project Orbiter, to put a scientific satellite into orbit during the International Geophysical Year. However, this proposal was rejected in 1955 by the Eisenhower administration in favor of the U.S. Navy's Project Vanguard.[7] Following the launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957, the initial Project Orbiter program was revived as the Explorer program to catch up with the Soviet Union, beginning the Space Race.[8]

Explorer 1 was designed and built by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), while the Jupiter-C rocket was modified by the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) to accommodate a satellite payload, the resulting rocket becoming known as the Juno I. The Jupiter-C design used for the launch had already been flight-tested in nose cone reentry tests for the Jupiter IRBM and was modified into Juno I. Working closely together, ABMA and JPL completed the job of modifying the Jupiter-C and building the Explorer 1 in 84 days. However, before work was completed the Soviet Union launched a second satellite, Sputnik 2, on November 3, 1957. The U.S. Navy's attempt to bring the first U.S. satellite into orbit failed with the launch of the Vanguard TV3 on December 6, 1957.[9]

Orbit

The Juno I rocket was launched putting Explorer 1 into orbit, which made Explorer 1 the first Earth satellite of the United States. The orbit had a perigee of 358 kilometers (222 mi) and an apogee of 2,550 kilometers (1,585 mi) having a period of 114.8 minutes.[2][3][4] At about 1:30 A.M. EST, after confirming that that Explorer 1 was indeed in orbit, a press conference was held at the National Academy of Sciences in the Great Hall to announce it to the world.[10]

The Explorer 1 payload consisted of the Iowa Cosmic Ray Instrument without a tape data recorder which was not modified in time to make it onto the Explorer 1. The real-time data received on the ground was therefore very sparse and puzzling showing normal counting rates and no counts at all. The later Explorer 3 launch, which included a tape data recorder in the payload, provided the additional data for confirmation of the earlier Explorer 1 data.

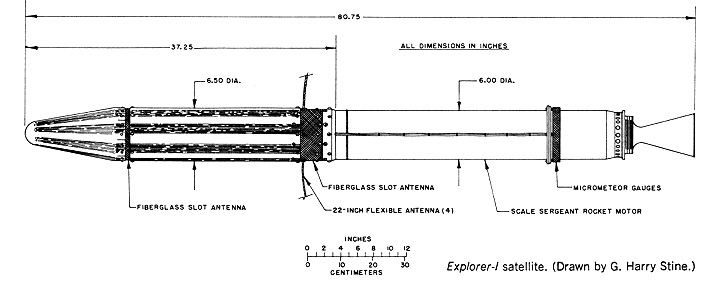

The total weight of the satellite was 13.97 kilograms (30.80 lb), of which 8.3 kg (18.3 lb) were instrumentation. In comparison the first Soviet satellite Sputnik 1 weighed 83.6 kg (184 lb). The instrument section at the front end of the satellite and the empty scaled-down fourth-stage rocket casing orbited as a single unit, spinning around its long axis at 750 revolutions per minute.

Spacecraft design

Explorer 1 was designed and built by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of the California Institute of Technology under the direction of Dr. William H. Pickering. It was the second satellite to carry a mission payload (Sputnik 2 was the first). The scientific instrumentation of the Explorer 1 satellite was designed and built under the direction of Dr. James Van Allen of the University of Iowa containing:[11]

- Anton 314 omnidirectional Geiger-Müller tube, designed by Dr. George Ludwig of Iowa's Cosmic Ray Laboratory, to detect cosmic rays. It could detect protons with E > 30 MeV and electrons with E > 3 MeV. Most of the time the instrument was saturated;[12]

- Five temperature sensors (one internal, three external and one on the nose cone);

- Acoustic detector (crystal transducer and solid-state amplifier) to detect micrometeorite (cosmic dust) impacts. It responded to micrometeorite impacts on the spacecraft skin in such way that each impact would be a function of mass and velocity. Its effective area was 0.075 m2 and the average threshold sensitivity was 2.5 × 10−3 g cm/s;[13][14] and

- Wire grid detector, also to detect micrometeorite impacts. It consisted of 12 parallel connected cards mounted in a fiberglass supporting ring. Each card was wound with two layers of enameled nickel alloy wire with a diameter of 17 µm (21 µm with the enamel insulation included) in such way that a total area of 1 cm by 1 cm was completely covered. If a micrometeorite of about 10 µm impacted, it would fracture the wire, destroy the electrical connection, and thus record the event.[13][14]

Because of the limited space available and the requirements for low weight, the Explorer 1 instrumentation was designed and built with simplicity and high reliability in mind. Electrical power was provided by mercury chemical batteries that made up approximately 40% of the payload weight.

Data from the scientific instruments was transmitted to the ground by two antennas. A 60 milliwatt dipole antenna consisting of two fiberglass slot antennas in the body of the satellite operating on 108.03 MHz, and four flexible whips forming a 10 milliwatt turnstile antenna operating on 108.00 MHz.[11][15]

The Explorer 1 instrumentation payload used transistor electronics, consisting of both germanium and silicon devices. This was a very early time frame in the development of transistor technology, and represents the first documented use of transistors in the U.S. Earth satellite program.[16] A total of 29 transistors were used in Explorer 1, plus additional ones in the Army's micrometeorite amplifier.

The external skin of the instrument section was painted in alternate strips of white and dark green to provide passive temperature control of the satellite. The proportions of the light and dark strips were determined by studies of shadow-sunlight intervals based on firing time, trajectory, orbit, and inclination.

Mission results

To the surprise of mission experts, satellite Explorer 1 changed rotation axis after launch. The elongated body of the spacecraft had been supposed to spin about its long (least-inertia) axis but refused to do so, and instead started precessing due to energy dissipation from flexible structural elements. Later it was understood that on general grounds, the body ends up in the spin state that minimizes the kinetic rotational energy (this being the maximal-inertia axis). This motivated the first further development of the Eulerian theory of rigid body dynamics after nearly 200 years - to address this kind of energy and momentum dissipation.[18][19]

Sometimes the instrumentation would report the expected cosmic ray count (approximately thirty counts per second) but sometimes it would show a peculiar zero counts per second. The University of Iowa (under Dr. Van Allen) noted that all of the zero counts per second reports were from an altitude of 2,000+ km (1,250+ miles) over South America, while passes at 500 km (310 miles) would show the expected level of cosmic rays. Later, after Explorer 3, it was concluded that the original Geiger counter had been overwhelmed ("saturated") by strong radiation coming from a belt of charged particles trapped in space by the Earth's magnetic field. This belt of charged particles is now known as the Van Allen radiation belt. The discovery of the Van Allen Belts by the first few Explorer satellites was considered to be one of the outstanding discoveries of the International Geophysical Year.

The acoustic micrometeorite detector detected 145 impacts of cosmic dust in 78,750 seconds. This calculates to an average impact rate of 8.0 × 10-3 impacts per m−2 s−1 over the twelve-day period (29 impacts per hour per square meter).[20]

The mercury batteries provided power that operated the high-power transmitter for 31 days and the low-power transmitter for 105 days. Explorer 1 stopped transmission of data on May 23, 1958,[21] when its batteries died, but remained in orbit for more than 12 years. It reentered the Earth atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean on March 19, 1970. Explorer 1 was the first of the long-running Explorer program, which as of April 2007 has launched 90 Explorer probes.

An identically-constructed flight backup of Explorer 1 is currently located in the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum, Milestones of Flight Gallery. A follow-up mission, Explorer-1 [PRIME], built using modern satellite construction techniques, is scheduled for launch in 2010.[22]

References

- ↑ Garber, Steve (October 10, 2007). "Explorer-I and Jupiter-C". NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/sputnik/expinfo.html. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Explorer 1 First U.S. Satellite - Fast Facts". JPL, NASA. http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/explorer/facts/. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Trajectory Details". NSSDC Master Catalog. NASA. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraftOrbit.do?id=1958-001A. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Solar System Exploration Explorer 1". NASA. http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/missions/profile.cfm?MCode=Explorer_01. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ↑ Yost, Charles W. (1963-09-06) (PDF). Registration data for United States Space Launches. United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. http://www.oosa.unvienna.org/pdf/inf044E.pdf. Retrieved 2009-02-19.

- ↑ Paul Dickson, Sputnik: The Launch of the Space Race. (Toronto: MacFarlane Walter & Ross, 2001), 190.

- ↑ "Project Vanguard - Why It Failed to Live Up to Its Name". Time (magazine). October 21, 1957. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,937919-1,00.html. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ↑ "Sputnik and The Dawn of the Space Age". NASA History. NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/sputnik/. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ McLaughlin Green, Constance; Lomask, Milton (1970). "Chapter 11: From Sputnik I to TV-3". Vanguard - A History. NASA. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4202/cover.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ "Discovering Earth's Radiation Belts: Remembering Explorer 1 and 3". NASA History. American Geological Union. 2008. http://www.agu.org/eos_elec/. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Explorer-I and Jupiter-C". Data Sheet. Department of Astronautics, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution. http://history.nasa.gov/sputnik/expinfo.html. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ↑ "Cosmic-Ray Detector". NSSDC Master Catalog. NASA. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/experimentDisplay.do?id=1958-001A-01. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Micrometeorite Detector". NSSDC Master Catalog. NASA. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/experimentDisplay.do?id=1958-001A-02. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Manring, Edward R. (January 1959). "Micrometeorite Measurements from 1958 Alpha and Gamma Satellites" (fee required). Planetary and Space Science (Great Britain: Pergamon Press) 1: 27–31. doi:10.1016/0032-0633(59)90019-4. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1959P&SS....1...27M. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Williams, Jr., W.E. (April 1960). "Space Telemetry Systems" (fee required). Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers (IEEE) 48 (4): 685–690. doi:10.1109/JRPROC.1960.287448. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpls/abs_all.jsp?isnumber=4066036&arnumber=4066076&count=63&index=39. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ "The First Transistors in Space - Personal Reflections by the Designer of the Cosmic Ray Instrumentation Package for the Explorer I Satellite". A Transistor Museum Interview with Dr. George Ludwig. The Transistor Museum. http://semiconductormuseum.com/Transistors/LectureHall/Ludwig/Ludwig_Index.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- ↑ "Astronomy Picture of the Day on January 31, 2008". Marshall Space Flight Center, NASA. 2008-01-31. http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/ap080201.html. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ↑ Efroimsky, Michael (August 2001). "Relaxation of wobbling asteroids and comets - theoretical problems, perspectives of experimental observation" (fee required). Planetary and Space Science (Elsevier) 49 (9): 937–955. doi:10.1016/S0032-0633(01)00051-4. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6V6T-43GH08G-5&_user=499905&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000024538&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=499905&md5=8414f735d59d3603c9ee3dd8baa09db2. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- ↑ Efroimsky, Michael (March 2002). "Euler, Jacobi, and missions to comets and asteroids" (fee required). Advances in Space Research (Elsevier) 29 (5): 725–734. doi:10.1016/S0273-1177(02)00017-0. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/els/02731177/2002/00000029/00000005/art00017. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Dubin, Maurice (January 1960). "IGY Micrometeorite Measurements" (fee required). Space Research - Proceedings of the First International Space Science Symposium (Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company) 1 (1): 1042–1058. http://stinet.dtic.mil/oai/oai?verb=getRecord&metadataPrefix=html&identifier=ADA285101. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ↑ Zadunaisky, Pedro E. (October 1960) (fee required). The Orbit of Satellite 456 Alpha (Explorer I) during the First 10500 Revolutions. Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1960SAOSR..50.....Z. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ↑ Byers, Celena. "Explorer-1 [Prime]: A Re-flight of the Explorer-1 Science Mission". Montana State University. http://atl.calpoly.edu/~bklofas/Presentations/DevelopersWorkshop2008/session6/2-Explorer1-Celena_Byers.pdf. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

External links

- Explorer 1 page on ispyspace.com

- Explorer 1 Mission Profile on NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- NASA's 50th Anniversary of the Space Age including Explorer 1 - Interactive Media

- Data Sheet, Department of Astronautics, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||